Red Hat Blog

For those of us who write a lot, there is a certain bias for the notion that "if you don't write it down, it didn't happen." It's not just writers; as digital as our world has become, there is still a value of permanence to the written word--it's just more likely in bytes rather than paper.

For those of us who write a lot, there is a certain bias for the notion that "if you don't write it down, it didn't happen." It's not just writers; as digital as our world has become, there is still a value of permanence to the written word--it's just more likely in bytes rather than paper.

In free and open source software communities, there's always a lot of stock put into the need to have written documentation of most any sort. From user guides, to feature specs, to marketing materials, a community's collective shared knowledge should not rely on the memory and experience of a few people in the community, but rather information that's freely available to all.

This may be preaching to the choir, of course, since the need for documentation is well established. Of course, getting that documentation created can be a challenge in and of itself. Many are the tales of project after project that could really take off in terms of adoption and contribution, except people are held back because they don't know enough about it or the learning curve is too steep. Arguing the pros and cons of documentation is not, however, the point of this discussion. Let's assume that this journey is underway and you are producing documents for your community.

Now the question becomes: what do you do with them?

Stuck On You

The problem that sometimes crops up within communities is that documents tend to be sticky. Specifically, they stick with the author/creator of the document. This is usually not a result of people being intentionally selfish. I have been guilty of this myself at times. I finish up a nice howto on using a new software feature and then I send a notice of its location on Google Drive or Dropbox out to a team or community by email. The document is received with some gratitude, and life goes on.

Until this happens: the email drops in my inbox that reads "Hey, Brian, where's that howto you wrote on the feature X a while back?"

At that exact moment, you have a document problem.

The problem is not that you don't have a document available... the issue is that it's not stored in a way that everyone who needs to find it can find it easily. Sure, I was cool and I published the document on [Insert Cloud Platform Here], but I likely posted to my account's space within that larger cloud platform. The document is still public, but it's still associated with me. It is, in effect, sticky.

This happens all of the time: slides, documents, and spreadsheets are scattered hither and yon throughout your community. They are publicly shared, but their accessibility is fragmented across multiple locations based on authors.

This may seem like a non-issue to some of you, because come on, how hard is it for people to just search their email for "sender: Brian feature X"? Indeed, I suspect many of us have gotten used to using our inboxes as ad hoc card catalogs where we try go call up enough keywords to find the information or document we need. But such searches, while occasionally valid, still rely on very specific institutional knowledge. What about, for instance, the community member who wasn't active in the community when you first sent out your document? If they don't ask around, they might assume that such a document was never made, and will either try to move on without it or, worse, duplicate effort and make their own version of the document.

Consolidation Is Key

The solution here is to try to gather all of the known documentation into one single repository that is prominently located within your community so anyone in your project should be able to find it. Additionally, that repository should be easily searchable so specific contents can be quickly located.

The type of repository does not matter: it can be GitHub, a community wiki, or even Google Drive. The important thing is that it's one repository for all documents... not many repositories for all documents.

This may seem dead obvious, but the truth is that even communities that have made a commitment to create documentation do not consistently archive their materials in this manner. Paradoxically, it's almost one of those things that seems so obvious that you don't have to do it. But the benefits of a central repository are clear:

- Project knowledge is more broadly shared

- Institutional knowledge is reduced

- Document consolidation can help identify gaps in coverage and versions

- Document collections can motivate the creation of more documents

It is important to note that you should not just dump your documents into a centralized repo and call it a day. Effective organization, such as through tagging, is another vital part of making such archives work. Sometimes archive users don't know the right search question to ask, so the more they can narrow their search down to the right content, the better.

Getting documentation right is a big enough challenge... don't make it hard for people to find what you do have.

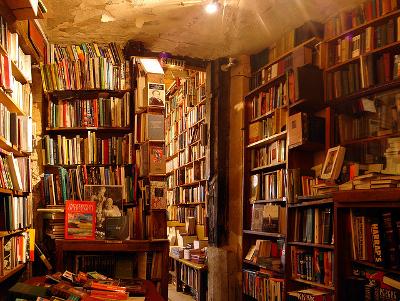

(Image courtesy Alexandre Duret-Lutz, (CC BY-SA 2.0))

Über den Autor

Brian Proffitt is Senior Manager, Community Outreach within Red Hat's Open Source Program Office, focusing on enablement, community metrics and foundation and trade organization relationships. Brian's experience with community management includes knowledge of community onboarding, community health and business alignment. Prior to joining Red Hat in 2013, he was a technology journalist with a focus on Linux and open source, and the author of 22 consumer technology books.