This post demonstrates my approach to build daily LLVM snapshot packages for Fedora using GitHub Actions, Python, package blueprints (RPM .spec files) and Fedora Copr as the build infrastructure. We’ll walk through various differences between a regular released version of LLVM and a snapshot release.

A typical LLVM release

The release manager for LLVM creates source tarballs with every new release of LLVM. That is more or less the result of a git archive operation on a particular directory in the LLVM mono-repository. In the downstream Fedora operating system we take those source tarballs and use them as input to our build system.

Building in standalone mode

There is a major difference between building LLVM as a developer and as a packager. As a developer you typically have one build location in which you build everything that you configured LLVM with.

As packagers for Fedora, my colleagues and I build LLVM piece by piece in isolation or standalone mode. That means when we for example build clang, the build system only sees the source code for clang not for llvm. Of course it sees llvm’s header files and the libraries but nothing more. The blueprint (aka RPM .spec file) for how to build clang then explicitly states that it requires llvm to build:

Notice the “BuildRequires: llvm-devel = %{version}” in line 113.

Among other things, building in standalone mode has the advantage of shorter build times and reduced Quality Engineering (QE) effort for us.

As with most operating system distributions out there, you cannot always be at the bleeding edge with the tools that you ship. In order to provide users with more recent versions of LLVM, we decided to build daily snapshots for the latest version of Fedora, namely 34, 35 and rawhide. The architectures that we started to build for are x86_64, ppc64le, aarch64, s390x and i386.

Minimal changes

In order to make it easier for us to migrate to the next official version of LLVM, I tried to keep the changes to the original blueprints for a package to a minimum.

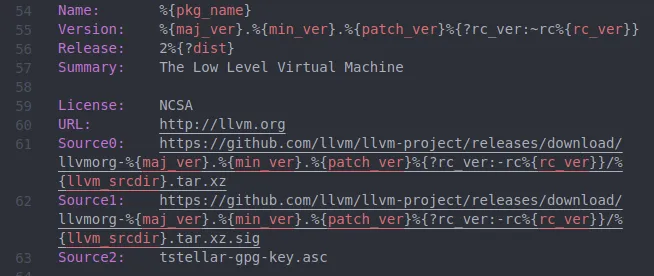

That required some thinking because spec files are the easiest to consume when you have a source tarball to work with:

See the line that begins with Source0:. It specifies what source tarball to download from the official LLVM release page.

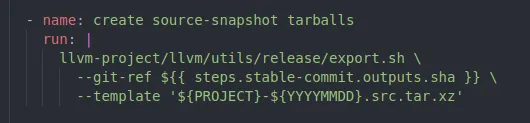

In order to provide such a tarball for daily snapshots I’ve made upstream LLVM changes to the llvm/utils/release/export.sh script that generates the tarballs and that is used by the release manager: https://reviews.llvm.org/D101446. It now lets you easily specify a git reference (e.g. a SHA-1 hash or a branch/tag name) and that will determine the next source tarball’s content. Before you could only specify which released version you wanted to create tarballs for.

This graphic shows how I use this export script in order to generate a tarball for a “stable” snapshot:

It is part of a Github Action called generate-snapshot-tarballs.yml that lives in a separate repository and schedules the creation of snapshot tarballs. It is separate for now but could easily be integrated into the upstream LLVM repository. But we decided to first show how one could use it before.

If the generate-snapshot-tarballs workflow completed successfully, then another workflow kicks in which is called fedora-copr-build. This workflow talks to the Fedora Copr (Community Projects) system to kick-off builds which you can monitor here:

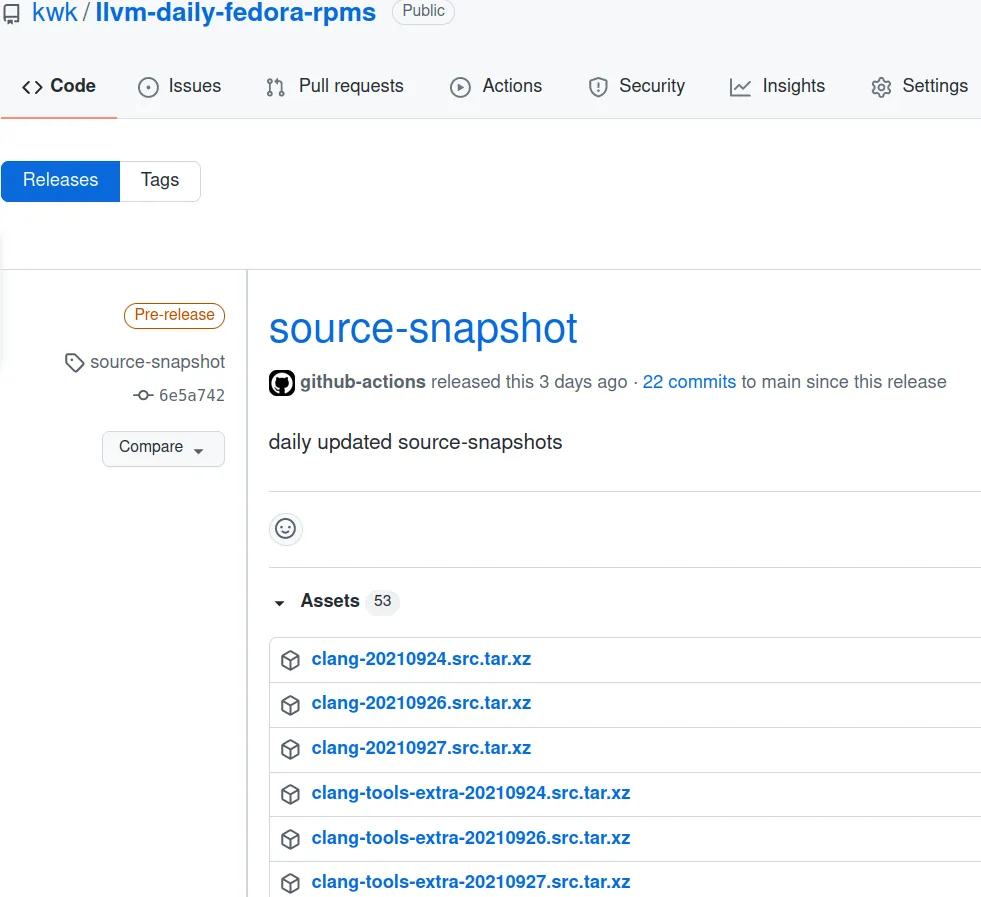

How snapshots are released

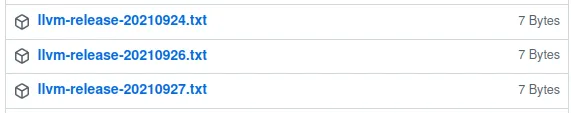

The source tarballs look like this once they got released to a dedicated pre-release on GitHub:

The pre-release entitled “source-snapshot” keeps the latest seven days of source snapshots before it starts to clean things up. I’ve made this a pre-release because this allows us to update this release without showing it up on the frontpage of the GitHub project. There, you’ll only see the latest regular release, but no pre-releases. This lets us constantly update the “source-snapshot” release and still “fly under the radar."

Currently I host this in my own repository but I will propose to add this mechanism to the official llvm-project.

Gotchas

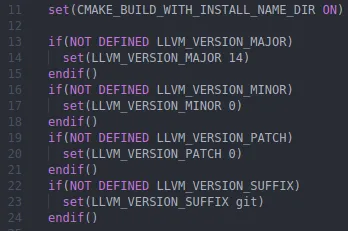

There’s one gotcha with building in standalone mode: Only the llvm package knows about its version because it is encoded in the CMakeLists.txt file of the llvm sub-project:

No other package knows about this. That is why I also always create a file llvm-release-YYYYMMDD.txt (YYYY being the year, MM being the month, and DD being the day.) alongside the source tarballs that knows about the version or the git commit hash for example. The build script can then do a `curl` on that file and download the version information for you.

The same is true for the reverse: When you only know the date a snapshot is created, but you need to know the git revision. That’s why I also release the file llvm-git-revision-YYYYMMDD.txt.

For us in Fedora it only makes sense to do daily builds for Fedora because the build times are so long. That is the reason why I named the source tarballs after the date they have been created. For maintenance this makes things so much easier. After all you can immediately tell what date it was yesterday but you don’t know right away the git SHA-1 of the time a snapshot was taken yesterday.

Check first

Another gotcha is that one can build LLVM and it fails because some test is broken by the time you took a snapshot. This is especially annoying when you know those post-merge errors typically get fixed very quickly. In upstream we have multiple checks that are reported on each commit:

We make sure that each snapshot we select for packaging, does pass the clang-x86_64-debian-fast and llvm-clang-x86_64-expensive-checks-debian tests. If a git commit doesn’t pass these tests we will recursively walk up to the parent commit until we find one that does pass.

Lessons learned

One thing I would like to point out is a lesson that I learned while weaving all the components together in Github Actions: I’ve been using PyGithub for the communication with Github and it struck me how easy it was until I’ve created a Github Action step with a Python shell. That way you can write the Python code directly in the Github Action YAML file. But this is not cool for testing. Instead I’ve created small little standalone Python programs that I call from the Github Action step. For example, here’s the script that takes care of deleting old snapshots:

By making it a simple standalone script I can run it from outside the context of a github action and test it.

Outlook

I intend to invest some time in experimenting with a tool called rpkg that is natively supported by Fedora Copr and lets us store the *.spec files in subdirectories of a full LLVM monorepo mirror. This way we could potentially get rid of manual patch file management or invoking “git format patch” all the time.

Instead all of our patches would become just a regular git commit on top of the LLVM upstream git repository. We can still build the LLVM projects in standalone mode. But instead of having git repos for each LLVM project with a branch for each Fedora version inside, we might just have one LLVM mono-project with the Fedora version branches inside.

Thank you for reading!

Sobre el autor

Konrad Kleine is a dad, husband and music lover, and he's worked for Red Hat since 2016.

Más como éste

How DTCC uses GitOps to accelerate customer value and security

Northrop Grumman scales enterprise Kubernetes for AI and hybrid cloud with Red Hat OpenShift

Diving for Perl | Command Line Heroes

The Ground Floor | Compiler: Tales From The Database

Navegar por canal

Automatización

Las últimas novedades en la automatización de la TI para los equipos, la tecnología y los entornos

Inteligencia artificial

Descubra las actualizaciones en las plataformas que permiten a los clientes ejecutar cargas de trabajo de inteligecia artificial en cualquier lugar

Nube híbrida abierta

Vea como construimos un futuro flexible con la nube híbrida

Seguridad

Vea las últimas novedades sobre cómo reducimos los riesgos en entornos y tecnologías

Edge computing

Conozca las actualizaciones en las plataformas que simplifican las operaciones en el edge

Infraestructura

Vea las últimas novedades sobre la plataforma Linux empresarial líder en el mundo

Aplicaciones

Conozca nuestras soluciones para abordar los desafíos más complejos de las aplicaciones

Virtualización

El futuro de la virtualización empresarial para tus cargas de trabajo locales o en la nube