Perhaps you've been charged with developing a container-based application infrastructure? If so, you most likely understand the value that containers can provide to your developers, architects, and operations team. In fact, you've likely been reading up on containers and are excited about exploring the technology in more detail. However, before diving head-first into a discussion about the architecture and deployment of containers in a production environment, there are three important things that developers, architects, and systems administrators, need to know:

- All applications, inclusive of containerized applications, rely on the underlying kernel

- The kernel provides an API to these applications via system calls

- Versioning of this API matters as it’s the “glue” that ensures deterministic communication between the user space and kernel space

While containers are sometimes treated like virtual machines, it is important to note, unlike virtual machines, the kernel is the only layer of abstraction between programs and the resources they need access to. Let’s see why.

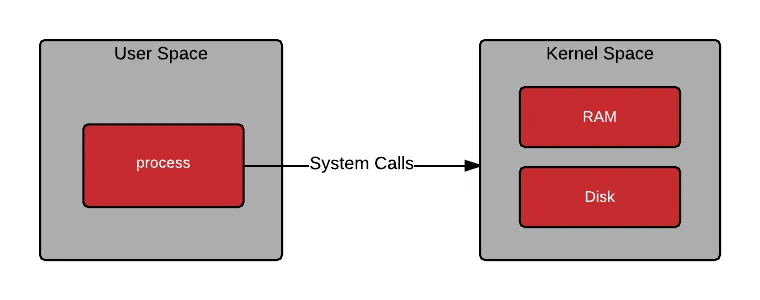

All processes make system calls:

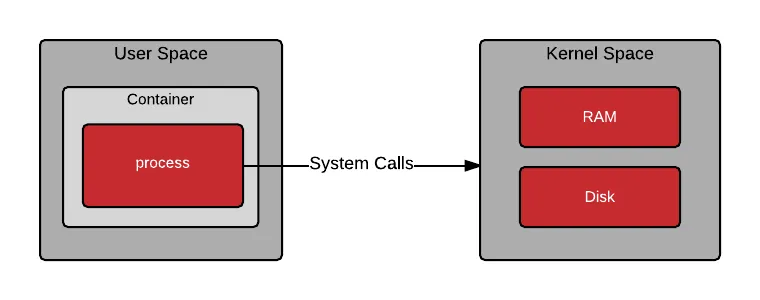

As containers are processes, they also make system calls:

OK, so you understand what a process is, and that containers are processes, but what about the files and programs that live inside a container image? These files and programs make up what is known as user space. When a container is started, a program is loaded into memory from the container image. Once the program in the container is running, it still needs to make system calls into kernel space. The ability for the user space and kernel space to communicate in a deterministic fashion is critical.

Vous souhaitez en faire plus avec les images UBI (Universal Base Images) de Red Hat ?

Vous souhaitez en faire plus avec les images UBI (Universal Base Images) de Red Hat ?

Vous souhaitez en faire plus avec les images UBI (Universal Base Images) de Red Hat ?

Vous souhaitez en faire plus avec les images UBI (Universal Base Images) de Red Hat ?

User Space

User space refers to all of the code in an operating system that lives outside of the kernel. Most Unix-like operating systems (including Linux) come pre-packaged with all kinds of utilities, programming languages, and graphical tools - these are user space applications. We often refer to this as “userland.”

Userland applications can include programs that are written in C, Java, Python, Ruby, and other languages. In a containerized world, these programs are typically delivered in a container image format such as Docker. When you pull down and run a Red Hat Enterprise Linux 7 container image from the Red Hat Registry, you are utilizing a pre-packaged, minimal Red Hat Enterprise Linux 7 user space which contains utilities such as bash, awk, grep, and yum (so that you can install other software).

docker run -i -t rhel7 bash

All user programs (containerized or not) function by manipulating data, but where does this data live? This data can come from registers in the CPU and external devices, but most commonly it is stored in memory and on disk. User programs get access to data by making special requests to the kernel called system calls. Examples include allocating memory (variables) or opening a file. Memory and files often store sensitive information owned by different users, so access must be requested from the kernel through system calls.

Kernel Space

The kernel provides abstraction for security, hardware, and internal data structures. The open() system call is commonly used to get a file handle in Python, C, Ruby and other languages. You wouldn’t want your program to be able to make bit level changes to an XFS file system, so the kernel provides a system call and handles the drivers. In fact, this system call is so common that is part of the POSIX library.

Notice in the following drawing that bash makes a getpid() call which requests its own process identity. Also, notice that the cat command requests access to /etc/hosts with a file open() call. In the next article, we will dig into how this works in a containerized world, but notice that some code lives in user space, and some lives in the kernel.

Regular user space programs evoke system calls all the time to get work done, for example:

ls ps top bash

These are some user space programs that map almost directly to system calls, for example:

chroot sync mount/umount swapon/swapoff

Digging one layer deeper, the following are some example system calls which are invoked by the above listed programs. Typically these functions are called through libraries such as glibc, or through an interpreter such as Ruby, Python, or the Java Virtual Machine.

open (files) getpid (processes) socket (network)

A typical program gets access to resources in the kernel through layers of abstraction similar to the following diagram:

To get a feel for what system calls are available in a Linux kernel, check out the syscalls man page. Interestingly, I am invoking this command on my Red Hat Enterprise Linux 7 laptop, but I am using a Red Hat Enterprise Linux 6 container image (aka user space) because I want to see system calls which were added/removed in the older kernel:

docker run -t -i rhel6-base man syscalls

SYSCALLS(2) Linux Programmer’s Manual SYSCALLS(2) NAME syscalls - Linux system calls SYNOPSIS Linux system calls. DESCRIPTION The system call is the fundamental interface between an application and the kernel. System call Kernel Notes ------------------------------------------------------------------------------ _llseek(2) 1.2 _newselect(2) _sysctl(2) accept(2) accept4(2) 2.6.28 access(2) acct(2) add_key(2) 2.6.11 adjtimex(2) afs_syscall(2) Not implemented alarm(2) alloc_hugepages(2) 2.5.36 Removed in 2.5.44 bdflush(2) Deprecated (does nothing) since 2.6 bind(2) break(2) Not implemented brk(2) cacheflush(2) 1.2 Not on i386

Notice from the man page, that certain system calls (aka interfaces) have been added and removed in different versions of the kernel. Linus Torvalds et. al. take great care to keep the behavior of these system calls well understood and stable. As of Red Hat Enterprise Linux 7 (kernel 3.10), there are 382 syscalls available. From time to time new system calls are added, and old system calls are deprecated; this should be considered when thinking about the lifecycle of your container infrastructure and the applications that will run within it.

Conclusion

There are some important take aways that you need to understand about the user space and kernel space:

- Applications contain business logic, but rely on system calls.

- Once an application is compiled, the set of system calls that an application uses (i.e. relies upon) is embedded in the binary (in higher level languages, this is the interpreter or JVM).

- Containers don’t abstract the need for the user space and kernel space to share a common set of system calls.

- In a containerized world, this user space is bundled up and shipped around to different hosts, ranging from laptops to production servers.

- Over the coming years, this will create challenges.

Over time, it will be challenging to guarantee that a container built today will run on the container hosts of tomorrow. Imagine the year is 2024 (maybe we’ll finally have real hoverboards) and you still have a container-based application that requires a Red Hat Enterprise Linux 7 user space running in production. How can you safely upgrade the underlying container host and infrastructure? Will the containerized application run equally well on any of the latest greatest container hosts available in the market place?

In Architecting Containers Part 2: Why the User Space Matters, we will explore how the user space / kernel space relationship affects architectural decisions and what you can do to minimize these challenges.

À propos de l'auteur

Plus de résultats similaires

Simplifying modern defence operations with Red Hat Edge Manager

Maximizing your experience: Top 6 benefits of having a Red Hat account

Data Security And AI | Compiler

Data Security 101 | Compiler

Parcourir par canal

Automatisation

Les dernières nouveautés en matière d'automatisation informatique pour les technologies, les équipes et les environnements

Intelligence artificielle

Actualité sur les plateformes qui permettent aux clients d'exécuter des charges de travail d'IA sur tout type d'environnement

Cloud hybride ouvert

Découvrez comment créer un avenir flexible grâce au cloud hybride

Sécurité

Les dernières actualités sur la façon dont nous réduisons les risques dans tous les environnements et technologies

Edge computing

Actualité sur les plateformes qui simplifient les opérations en périphérie

Infrastructure

Les dernières nouveautés sur la plateforme Linux d'entreprise leader au monde

Applications

À l’intérieur de nos solutions aux défis d’application les plus difficiles

Virtualisation

L'avenir de la virtualisation d'entreprise pour vos charges de travail sur site ou sur le cloud