Since digital payments are becoming increasingly popular, users are perhaps more vulnerable to cybersecurity attacks than ever before. The answer to this increased risk? A self-sovereign identity (SSI)—especially for the financial services sector.

What is Digital Identity? Why is it important?

First, we need to understand what a digital identity is.

A digital identity is simply a collection of electronically stored features associated with a uniquely identifiable individual. Examples can include usernames and passwords, date of birth, and electronic transactions.

Typically, we establish multiple digital identities, including creating new accounts for each service provider we enroll with, or through third party login mechanisms like Facebook (although these are generally considered insecure for financial services).

Summarily, we establish a new account for each new sensitive service we sign up for. Consider two problems:

-

We create several identities with multiple providers, all different but each representing the same person—all of which are vulnerable to identity theft with no easy or standard way to verify them.

-

We have no way of knowing when our identity is used, by whom, or when/if to revoke consent to usage of that particular identity.

A self-sovereign identity (SSI) can help solve these problems. An SSI is a lifetime portable identity for any person, organization, or thing that does not depend on any centralized authority and can never be taken away.

The shift towards virtual: principal drivers toward a more secure digital identity

Over the duration of the pandemic, it became clear that digital identity became of paramount importance as an answer to ever-present security issues, and amplified them - especially for the financial services sector.

Concerns at the forefront of this industry participants include:

-

What current challenges are digital identity frameworks facing, and what might be on the horizon?

-

Why has the need for a new digital identity model emerged, and how might a solution to it take form?

Many companies were unprepared for the necessary changes in procedures and infrastructure associated with the wide acceptance of remote work.

Network providers were challenged by an unprecedented rising demand of traffic, and many service providers had difficulty anticipating and enabling the corresponding client increase.

Impacts of the pandemic on the consumer side were also immediate, including both quantifiable and behavioral elements. Already an established trend, the virtual consumption model has only accelerated in momentum, based on convenience, health perception/protection, and regulatory mandates. Fortunately, other businesses, with a less physical transaction model, were able to pivot and capitalize through an expanded e-commerce presence as a survival tactic.

Corresponding to these behaviors was the shift away from physical payments and cash, driven by these same tactical and strategic factors. Consider tangible and observational elements that included:

-

Significantly smaller proportion of payments being made in-person as isolation kept people at home.

-

Customers being advised to avoid cash for hygienic reasons and many businesses now discourage cash—or are reluctant to accept it.

-

Contactless cards and digital wallets seeing a spike in usage—reinforced by the preferred usage habits of newer generations. In the UK, for example, cash usage decreased by 50%.

Initiatives underway in some countries encourage the wider acceptance of a completely digital currency based on blockchain technology.

These observed phenomena are not only present in well developed countries, but exist globally, including those with less established economies. In these countries, telcos witnessed the biggest increase in usage, given the reliance on systems like M-Pesa. Many people in these countries are migrating directly from cash to mobile payments without ever owning a physical payment card.

The rise of cybercrime and contributing factors

Virtual transactions can be the target of another global growing trend: digital fraud and identity theft.

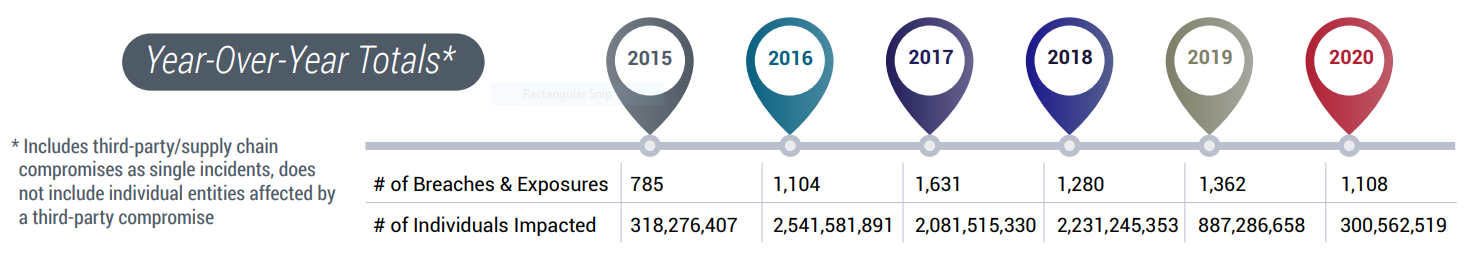

While the impact on individuals might be exhibiting a decline over the last two years, it is still sizable. According to the Identity Theft Resource Center, 300,562,519 individuals were impacted by publicly reported data breaches in 2020.

Cyber criminals are less interested in theft of consumer personal information, with a notable uptick in activities targeting lucrative businesses through stolen credentials such as logins and passwords.

Ransomware and phishing attacks require less effort, are largely automated, and generate payouts that are much higher than taking over the accounts of individuals. One ransomware attack can generate as much revenue in minutes as hundreds of individual identity theft attempts over months or years. The Identity Theft Resource Center also reports that the average ransomware payout was greater than $233,000 per event in the fourth quarter 2020.

Among the possible factors contributing to this rapid increase:

-

Customer vulnerabilities are exposed as they are forced to new payment methods and asked to rely on and trust third parties.

-

Confidence levels have been driven lower and social anxiety is higher, making individuals more susceptible to social engineering attacks as they turn to these channels.

-

Increased competition has compelled banks into a cost-cutting situation, where mitigating these categories of attacks mandates an additional technical (and technology investment) challenge. This also implies that there will be an increase in long-term investment in fraud detection.

-

As more and more services are moved online (in the form of e-commerce) and more businesses take advantage of embedded finance, a larger online perimeter is established in which malicious users can “play”—including offering more opportunities for attackers to build synthetic profiles from several data breaches, which are then utilized by applying illegally for a loan or for a credit card.

Regulatory impacts and their contribution towards the establishment of digital identity

Regulations across the financial services industry and in other sectors are pushing the innovation edge by necessity. While US-based entities are adhering to an enhanced regulatory framework, these mandates are particularly applicable in Europe, where there is necessary compliance with enacted standards (such as the General Data Protection Regulation—commonly known as GDPR—and the Payment Service Providers Directive 2—referred to as PSD2. A clear need for a true and persistent digital identity as a solution to the ancillary—and sometimes unforeseen—challenges that have arisen. While these challenges point to the need for a secure digital identity, Yet, in practice, we have already exposed ourselves unknowingly.

In the physical world, we’ve adopted standard and verifiable practices for obtaining and maintaining permanent identity-related documentation, such as a passport or driver’s license. Either of these documents are accepted globally as identification medium and they are trusted as such.

Can’t we replicate a parallel solution in the digital world as well?

Introducing Self Sovereign Identity (SSI)

Self-sovereign identity (SSI) is a term used to describe the digital movement that recognizes an individual should own and control their identity without the intervening administrative authorities.

Let’s start with identifying some of the acronyms used:

-

SSI: Self-Sovereign Identity

-

DID: Decentralized Identifiers

-

SSO: Self Sovereign OpenId Connect (not to be confused with Single Sign-On)

To understand our perspective as applied to these concepts, we’ll examine the three main models for identity management.

-

Centralized Identity or “siloed” identity is the simplest of the three models. An organization issues the digital credential to individuals or allows them to create it for themselves. Trust between the individual and the issuer is typically established through the use of shared private information: usually in the form of a username and password and sometimes additional information such as a PIN or security questions. Occasionally this information is augmented with additional factors such as physical tokens or biometrics.

-

Federated identity or IDP relationship model adds a third-party company or consortium, acting as an “identity provider” (IDP) between the individual and the issuer or service the individual is attempting to access. The IDP issues the digital credential, providing a single sign-on experience with the IDP that can seamlessly be used elsewhere—reducing the number of separate credentials a consumer needs to maintain.

-

A common example of the IDP model is “social login” on the web using Facebook, Google or other social IDs to access a third-party service. With social login, one of these tech giants serves as the IDP, but this option is acceptable only in lower-trust environments (such as e-commerce) and not in a high-trust one such as banking.

-

-

Self-sovereign identity (SSI) is a two-party relationship model, with no third party coming between the individual and the issuer. SSI begins with a digital “wallet” that contains digital credentials. It acts like a physical wallet where a consumer carries credentials issued by others, such as a passport or driver’s license.

The four basic flows and elements involved in this model, consisting of:

-

Decentralized IDentifiers: you will likely have multiple DIDs according to which issuer you identify from. Each one will give you a lifetime encrypted private channel with another person, organization, or other entity. You will use it not just to prove your identity, but to exchange verifiable digital credentials and aiding in its simplicity and security: there will be no central registration authority, as every DID is registered directly on a blockchain or distributed network.

-

Decentralized Key Management System: a proposed open standard for managing the private keys you need for DIDs, which includes robust, highly usable key recovery. DKMS key recovery supports both offline recovery (“paper wallet”) and social recovery (“trustee”) methods.

-

DID Auth: a simple standard way for a DID owner to authenticate by proving control of a private key.

-

Verifiable credentials: the format for interoperable, cryptographically-verifiable digital credentials being defined by the W3C Verifiable Claims Working Group.

Using SSI in the real world

Sean Brown, Program Director, IBM Security, presented a real-world use case at the 2020 Data Center World Conference. He examined how our fictional person, “Alice”, leveraging her newly acquired college degree, can swiftly apply to a new job at Acme Corporation, and subsequently apply for a loan, while continuously maintaining complete control and management over her identity.

Upon graduation, Alice is issued a transcript (DID Auth) which she can use to apply for employment. Alice stores these credentials in her digital wallet (DKMS) which resides in a distributed ledger.

-

Alice presents credentials from her wallet when she needs to prove her identity in a peer-to-peer interaction.

-

Acme Corp uses decentralized identifiers and verifiable credentials (DID) from the distributed ledger to perform identity verifications to greatly simplify processing, and upon successful employment, issues a job certificate certificate.

The same flow happens where Alice applies for a loan, leveraging her newly acquired job verifiable credentials.

-

Alice presents a job certificate, and other necessary information to her prospective bank.

-

The bank verifies the criteria for authenticity and accuracy via the distributed ledger, and is able to issue an account certificate to Alice.

As these events transpire, Alice will accumulate several DIDs according to which Peer she is identifying with (in this example Acme or her Bank) , and each Peer will release a new DID upon successful authentication and processing.

Most importantly, the distributed ledger component guarantees the greatly more efficient and an unforgeable format of authentication verification.

One last relevant element is the fact that Alice will disclose only the elements of her DID that are relevant to that specific interaction (for example, she might decide not to share her GPA with the bank when applying for the loan) because she has full control over it.

Where to go with SSI

In each instance where identity verification is part of a more complex process, there can be a drastic reduction in processing duration and increase in effectiveness.

Consumers will benefit in instances such as loan processing (with accompanying credit check verification) or when establishing a new bank account or a new internet contract (with identity and residency manual verification).

Service providers may benefit, as they will be able to minimize fraudulent account creation and simultaneously protect both parties from phishing attacks.

These advantages are not limited to business enterprises, as most services provided by public administration could be potentially moved online (assuming the procedure behind the web interface has been automated).

Additionally, these practices have the potential to open access to financial services for those presently not in possession of bank accounts (without the need to sign up for a full-fledged account). As an example, we refer to one of the first success cases of SSI to appear in the news: MyCash Money selects Onfido to power remittance services in Singapore and Malaysia with trusted identity verification.

Concluding remarks

Whether driven by new realities in consumer behavior that might become permanent, or taken in response to regulatory issues which hope to enhance security and limit fraudulent activity, the concept of robust digital identity has deservedly risen in importance.

The critical element and functionality of SSI revolves around Digital Identity Management, which typically is under the control of an identity platform—an example of which is Red Hat Single Sign-On.

To explore a case study example of how Red Hat’s Single Sign-On (SSO) technology utilized an access based identity repository in conjunction with our OpenShift product to solve a complex customer problem, we'd invite you to explore here.

À propos de l'auteur

Plus de résultats similaires

Attestation vs. integrity in a zero-trust world

From incident responder to security steward: My journey to understanding Red Hat's open approach to vulnerability management

Data Security 101 | Compiler

AI Is Changing The Threat Landscape | Compiler

Parcourir par canal

Automatisation

Les dernières nouveautés en matière d'automatisation informatique pour les technologies, les équipes et les environnements

Intelligence artificielle

Actualité sur les plateformes qui permettent aux clients d'exécuter des charges de travail d'IA sur tout type d'environnement

Cloud hybride ouvert

Découvrez comment créer un avenir flexible grâce au cloud hybride

Sécurité

Les dernières actualités sur la façon dont nous réduisons les risques dans tous les environnements et technologies

Edge computing

Actualité sur les plateformes qui simplifient les opérations en périphérie

Infrastructure

Les dernières nouveautés sur la plateforme Linux d'entreprise leader au monde

Applications

À l’intérieur de nos solutions aux défis d’application les plus difficiles

Virtualisation

L'avenir de la virtualisation d'entreprise pour vos charges de travail sur site ou sur le cloud