Stop me if you've heard this one.

Stop me if you've heard this one.

Open source project is licensed under License A, and someone comes along and requests/demands that License B be used instead. Conversation ensues, which soon becomes an all-out flame war, because Someone Is Wrong On the Internet.

It's a common enough occurrence that anyone who has interacted with the free and open source software (FOSS) communities for any length of time has surely witnessed it. Or perhaps even participated in such a flame war.

Just yesterday I saw a discussion on a bugtracker system for a project using an MIT license. The bug? Move the project to the GPL. The conversation unfolded pretty much as I described in the hypothetical described in the introductory paragraph, up to and including using a certain flamboyant U.S. politician as an updated representation of Godwin's Law.

The good news is, in this case, the conversation was reigned in by the project maintainers and eventually everyone got to the point that, while no new decisions were made, there was the sense that all sides of the discussion were heard.

Communicating online is not always easy. Even within the Open Source and Standards team, which is scattered across the world, we can have the occasional bump in the road as meaning is sometimes lost or misunderstood in mailing lists or IRC channels. It doesn't happen often, because we know each other, having met at various meetings and events over the years. We know each other's viewpoints and strange little quirks that define our humor, so it takes a lot to get really offended.

That same kind of familiarity exists in many FOSS projects as well—the older the project, the more institutional culture is set in place and (usually) the less friction there is in online discussions. But that only goes so far; the more active a project is, the more newcomers arrive asking all sorts of questions about issues that were resolved months or years ago and generally taxing everyone's patience.

Good.

There is a certain need in any project to distinguish between "the way things should be" versus "the way things have always been." The two concepts can often go hand-in-hand, but not always. Innovation lies in the instances where the status quo is questioned and the way things have always been are set aside and new ways take shape.

But there are better ways to ask such questions. If you go in with a chip on your shoulder and declarations that your way is the only way and the project's way is stupid, take a wild guess how well your ideas will be received. Instead, try a couple of techniques that may help get your voice heard.

-

Know Your Audience. Get to know the project and its active participants before setting about trying to make changes. Learn who the influencers are and find out if your idea is really something new, or something that has been discussed and decided upon before.

-

Be a Community Member. If you want people to listen and respect your voice, participating in the project is a great way of doing it. Just as you need to get to know them, they need to get to know you, learning your strengths and weaknesses and building trust.

-

Don't Try to Change the World. You're not the Brain, or Pinky for that matter. You don't have to try to make massive changes all at once. Start small, work towards your goal incrementally.

-

Listen. Don't be afraid to hear new ideas or critiques about your work. You may not have it right, whether by a mistake you've made or not knowing everything about the project. Either way, you're trying to be part of a team now and you don't want to hog the ball.

-

Avoid Nerd Rage. Tricky at times, because not all critiques are delivered with gentility and grace. But if a conversation goes bad, take a breath. Think about what the other person is trying to do. If you're right, keep pointing out what they may have misunderstood about your ideas.

It should be noted, by the way, that project maintainers and owners can take this ideas and apply them in the other direction: make it easy to learn a project's ins and outs, define contributor paths, set transparent project goals, listen, and avoid nerd rage. It goes both ways.

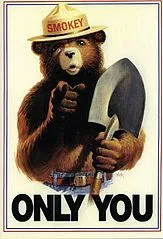

Online communication is hard, because social cues you get with face-to-face conversations are missing. But effective and consistent communications strategies can make life in FOSS easier and cut down on the flame wars.

(Image under U.S. government public domain.)

À propos de l'auteur

Brian Proffitt is Senior Manager, Community Outreach within Red Hat's Open Source Program Office, focusing on enablement, community metrics and foundation and trade organization relationships. Brian's experience with community management includes knowledge of community onboarding, community health and business alignment. Prior to joining Red Hat in 2013, he was a technology journalist with a focus on Linux and open source, and the author of 22 consumer technology books.

Plus de résultats similaires

Red Hat's commitment to the EU Cyber Resilience Act: Shaping the future of cybersecurity standards

Data-driven automation with Red Hat Ansible Automation Platform

Technically Speaking | Platform engineering for AI agents

Technically Speaking | Driving healthcare discoveries with AI

Parcourir par canal

Automatisation

Les dernières nouveautés en matière d'automatisation informatique pour les technologies, les équipes et les environnements

Intelligence artificielle

Actualité sur les plateformes qui permettent aux clients d'exécuter des charges de travail d'IA sur tout type d'environnement

Cloud hybride ouvert

Découvrez comment créer un avenir flexible grâce au cloud hybride

Sécurité

Les dernières actualités sur la façon dont nous réduisons les risques dans tous les environnements et technologies

Edge computing

Actualité sur les plateformes qui simplifient les opérations en périphérie

Infrastructure

Les dernières nouveautés sur la plateforme Linux d'entreprise leader au monde

Applications

À l’intérieur de nos solutions aux défis d’application les plus difficiles

Virtualisation

L'avenir de la virtualisation d'entreprise pour vos charges de travail sur site ou sur le cloud