By the time Red Hat customers run one of our products, it already has had a long history of development, testing, review, and other assorted refinements, both internally and across its many related upstream projects.

Most of our customers are happy to stay at their end of this long road, but for the curious, here's a high-level end-to-end overview. While this process will vary from upstream project to upstream project, the following is specific to glibc, including glibc's new CI/CD automated patch review system!

Legalese

Unfortunately, one of the first things to consider is the legality of your contribution. Are you allowed to share your work? Put away your scared-y face, this is mostly just understanding your situation and maybe filling out a form. The three most common options are:

No Legalese Required

Developer Certification of Origin

Assignment

If your contribution is short (15 lines or less, cumulative), it's considered a "legally insignificant" change by the glibc project and nothing special needs to be done legally. Note I said "cumulative" - two eight line patches would exceed this limit, regardless of how much time passes between submitting them.

If your contribution is larger than 15 lines, then the glibc project requires assurance that you have the legal right to contribute it. There are two ways to do this. One is to complete an assignment whereby you assign your change to the FSF, and usually your employer or school (or anyone else who might have claim on your work) will file a disclaimer allowing you to do so, and specifying what you're allowed to assign. The other assurance comes from a Developer Certificate of Origin where the contributor certifies for each patch that they may contribute it, by "signing" the patch:

Signed-off-by: Random J Developer <random@developer.example.org>

Dealing with the legal paperwork might be the most frustrating, feared, and lengthy part of the process, but it's an important first step. Once done, you have the right to contribute your patches to glibc! Depending on the results of this legal process it may cover future contributions as well, saving some future headaches.

Submittal Checklist

Now that you're past the legal issues, it's time to actually send in your patch. The glibc project maintains a fairly complete checklist for patch submissions but here's a summary:

Make sure your patch is complete and correct, including formatting.

Make sure your patch includes relevant documentation.

Make sure your patch is sufficiently tested.

Email your patch to the mailing list.

Wait for discussion or consensus.

The checklist covers these in detail, and they're only of interest if you actually submit a patch (in which case, you need to read the checklist anyway. The last one warrants some detail, though, which will be covered later in this article. But what happens next?

Automated Testing

The glibc project uses a system called Patchwork to manage its patches. You can see a list of our currently pending patches here.

This implies some rules about naming your patches (the subject in your emails). Patchwork can combine a multi-patch series into a single unit, or replace obsolete versions of your patch with a new version, if you and it agree on some conventions. As usual, these are all detailed in the checklist, but it boils down to a subject line like this (which you get by default with a tool like git-send-email):

[PATCH v1 1/4] malloc: fix a bug [BZ #123456]

This lets patchwork know where in the series it is (1/4, 2/4, etc) and which version it is (v1, v2, etc; increment this each time you update a patch, and remove any "Re:" from your subject line when you do, for we all know that "Re:" is short for "Reply:" and if you say it's a reply, it's a reply).

If you're fixing a bugzilla, include that in the subject too. Patchwork additionally keeps track of the state of the patches, like who is assigned to review them, or which checks have passed...

Checks, you say? Yes, there's a system of automated "checks" that run when you submit a patch, such as "does the patch apply cleanly?" or "does the patch build on a 32-bit system?" This custom CI/CD system listens to the Patchwork events and triggers a distributed set of machines which can run whatever validation checks or tests are desired.

CI/CD Overview

Our CI/CD (continuous integration, continuous delivery) system is a custom system designed for the not-quite-unique needs of our core development environment. Working on glibc is not glamorous, and the core developers have been around for a while. This means we're more comfortable working with email than with a GUI, hence the use of Patchwork, which is email-based. Our CI/CD system is based on Patchwork, and thus also email-based.

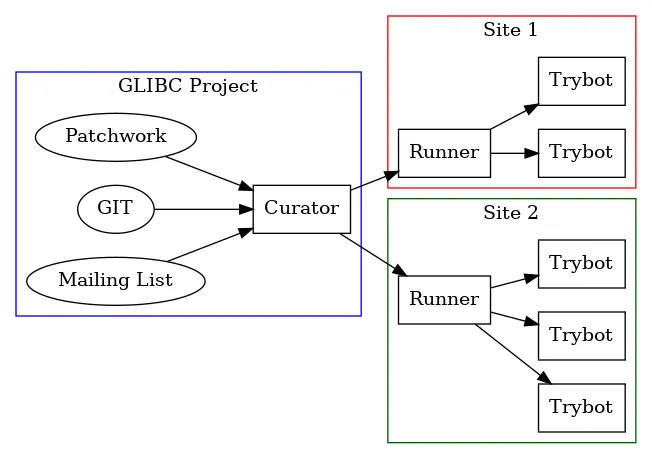

The design of this system is based on the premise that various members of the community will provide testing services that test aspects of each patch that interest them - i.e. they're scratching their respective itches. There's a central database that communicates with multiple remote testing sites.

The heart of the system is a module we call "the curator." As you might guess, the purpose of this module is to collect (or listen for) events from Patchwork (for proposed patches), our Git repo (for accepted patches), and the mailing list; and select which events are "interesting" for testing, and collect those along with ancillary information. There is one central curator which maintains a database of such interesting issues.

Each testing site maintains a module called a "runner," which is a bit of a misnomer as it doesn't "run" anything, but decides what should be run by that site. Based on the event data and local policy, the runner will, via a message queue, schedule zero or more local tests. Our philosophy is that the runner only makes decisions - it is how each site chooses its level of participation.

Listening to that message queue are one or more "trybots." Each one listens for a specific message, and when it gets that message, does whatever it's supposed to do - which could be anything from "check spelling" to "run a full suite of builds and tests." The results of these checks are reported back to the Patchwork system, and show up as color-coded pass/fail markers.

For further design internals, see the wiki "CI/CD for glibc" page.

Patch Reviews

Assuming your patch passes the automatic tests (above), the next step is to get someone to review it. This can often be the most frustrating part of the process (yes, even more so than the legal issues) as you need to first get someone's attention, and second resolve whatever issues they bring up. Often multiple times. With multiple people making different demands. With a little patience and a little perseverance, and possibly many versions of your patch, you'll eventually satisfy the reviewers and move on to the next step...

But who can review your patches? Anyone. It's a community! You can review patches too, if you feel comfortable doing so. Those who review and approve of your patch will add a "Reviewed-by:" line saying that they're OK with your patch:

Reviewed-by: Random J Developer <random@developer.example.org>

These approvals get copied into the git commit message, so there's a record of who reviewed your patch. If you change the patch (i.e. person A reviewed it, but person B noticed a problem with it), the previous Reviewed-by's no longer apply, and the patch needs a new review.

For more info, read about the patch process and our notes on patch review meetings.

Consensus

The glibc project uses a "consensus" model for approving patches, which can be tricky to understand, leaving a new contributor unsure if they should commit their patch or not. Basically, if you've got at least one successful review (i.e. each part N/M of your patch set has a Reviewed-by), and a couple of business days have passed without any complaints or further comment, you can assume you've got consensus for your patch, and your patch is approved. If anyone disagrees with your patch, it's up to you to resolve this disagreement somehow.

There's also a set of "trivial" patches that anyone can apply at any time; consensus is assumed. For example, spelling errors, sorting some lists in alphabetical order, fixing dates, etc. There's a list in glibc wiki if you'd like to read more.

Approved!

Congratulations! You've persevered, debugged, submitted, and won approval. Now you get to commit your patch... what? You don't have commit privileges? Asking nicely on the mailing list will usually get someone who does to commit it on your behalf. They'll be listed as the "committer" of the patch, and you'll be listed as the "author." Your patch is now an official part of glibc, and will be included in the next scheduled release.

Backports and Downstreams

But what if you need your patch elsewhere? There are two scenarios to consider: you need your patch in an older version of glibc, or you need it in some distribution that uses glibc.

The first case is called a backport. In general, any patch that's approved for the next release, is also approved for previous releases, but of course it's up to you to ensure that the patch works correctly in older releases. Note that "previous releases" includes the current release, which is where you'll most likely want it.

The second case refers to a downstream user of glibc. Normally, for example, a new version of glibc is released just before a new version of Fedora, so Fedora can get the latest version of glibc. Fedora is thus "downstream" of the main glibc project, and glibc is "upstream" of Fedora. Since RHEL is based on Fedora, RHEL is even further "downstream" of glibc.

These two cases are often related, as downstreams will often track one of the upstream release branches, so an upstream backport is also a downstream backport. To request a backport, post your patch (or a reference to it in glibc's Git) to the the libc-stable mailing list and begin a discussion there.

Summary

We don't expect most of our customers to contribute directly to our products this way - creating enterprise grade solutions is our strength - using them is your strength. Understanding how change happens is a kind of "knowing your supply chain", where your supply chain is much more open than usual, and welcomes volunteers.

À propos de l'auteur

DJ Delorie is a Principal Software Engineer at Red Hat.

Plus de résultats similaires

KServe joins CNCF as an incubating project

Bringing intelligent, efficient routing to open source AI with vLLM Semantic Router

Air-gapped Networks | Compiler

The Truth About Netcode | Compiler

Parcourir par canal

Automatisation

Les dernières nouveautés en matière d'automatisation informatique pour les technologies, les équipes et les environnements

Intelligence artificielle

Actualité sur les plateformes qui permettent aux clients d'exécuter des charges de travail d'IA sur tout type d'environnement

Cloud hybride ouvert

Découvrez comment créer un avenir flexible grâce au cloud hybride

Sécurité

Les dernières actualités sur la façon dont nous réduisons les risques dans tous les environnements et technologies

Edge computing

Actualité sur les plateformes qui simplifient les opérations en périphérie

Infrastructure

Les dernières nouveautés sur la plateforme Linux d'entreprise leader au monde

Applications

À l’intérieur de nos solutions aux défis d’application les plus difficiles

Virtualisation

L'avenir de la virtualisation d'entreprise pour vos charges de travail sur site ou sur le cloud