Shell scripts provide a very powerful feature: the ability to redirect the output from commands and scripts and send it to files, devices, or even as input to other commands or scripts.

This article focuses on command and script output.

Types of output

Commands and scripts in a shell can generate two basic types of outputs:

- STDOUT: The normal output from a command/script (file descriptor 1)

- STDERR: The error output from a command/script (file descriptor 2)

By default, STDOUT and STDERR are sent to your terminal's screen.

In terms of input, STDIN by default reads input from the keyboard (file descriptor 0). A file descriptor is a unique identifier for a file or other I/O resource.

How to redirect shell output

There are multiple ways to redirect output from shell scripts and commands.

1. Redirect STDOUT

For the following examples, I will use this simple set of files:

$ls -la file*

-rw-r--r--. 1 admin2 admin2 7 Mar 27 15:34 file1.txt

-rw-r--r--. 1 admin2 admin2 10 Mar 27 15:34 file2.txt

-rw-r--r--. 1 admin2 admin2 13 Mar 27 15:34 file3.txt

I'm running a simple ls commands to illustrate STDOUT vs. STDERR, but the same principle applies to most of the commands you execute from a shell.

I can redirect the standard output to a file using ls file* > my_stdout.txt:

$ls file* > my_stdout.txt

$ cat my_stdout.txt

file1.txt

file2.txt

file3.txt

Next, I run a similar command, but with a 1 before >. Redirecting using the > signal is the same as using 1> to do so: I'm telling the shell to redirect the STDOUT to that file. If I omit the file descriptor, STDOUT is used by default. I can prove this by running the sdiff command to show the output of both commands side by side:

$ls file* 1> my_other_stdout.txt

$sdiff my_stdout.txt my_other_stdout.txt

file1.txt file1.txt

file2.txt file2.txt

file3.txt file3.txt

As you can see, both outputs have the same content.

2. Redirect STDERR

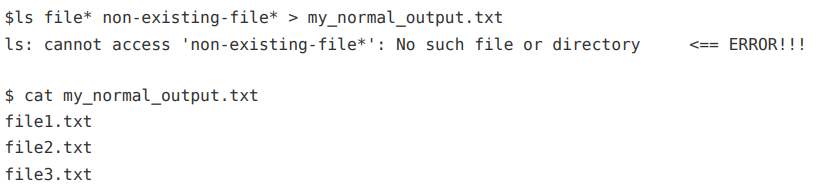

Now, what is special about STDERR? To demonstrate, I will introduce an error condition to the previous example with ls file* non-existing-file* > my_normal_output.txt:

Here's the result:

Here are some observations from the above test:

- The output about the existing files is sent correctly to the destination file.

- The error (which displays when I try to list something that does not exist) is sent to the screen. This is the default place errors are sent unless you redirect them.

[ Download a Bash Shell Scripting Cheat Sheet. ]

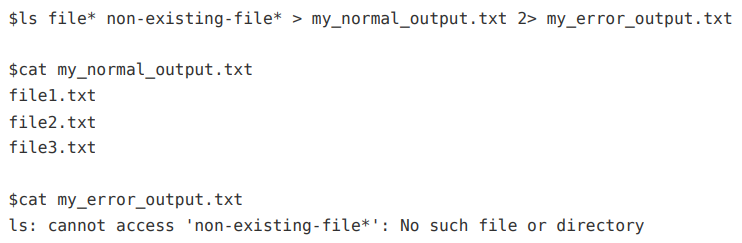

Next, I'll redirect the error output by referencing file descriptor 2 explicitly with ls file* non-existing-file* > my_normal_output.txt 2> my_error_output.txt:

In the example above:

- The

lscommand does not display the error message on the screen like before. - The normal output contains what I expect.

- The error message is sent to the

my_error_output.txtfile.

3. Send STDOUT and STDERR to the same file

Another common situation is to send both STDOUT and STDERR to the same file:

$ls file* non-existing-file* > my_consolidated_output.txt 2>&1

$ cat my_consolidated_output.txt

ls: cannot access 'non-existing-file*': No such file or directory

file1.txt

file2.txt

file3.txt

In this example, all output (normal and error) is sent to the same file.

The 2>&1 construction means "send the STDERR to the same place you are sending the STDOUT."

4. Redirect output, but append the file

In all the previous examples, whenever I redirected some output, I used a single >, which means "send something to this file, and start the file from scratch." As a result, if the destination file exists, it is overwritten.

If I want to append to an existing file, I need to use >>. If the file doesn't already exist, it will be created:

$echo "Adding stuff to the end of a file" >> my_output.txt

$cat my_output.txt

file1.txt

file2.txt

file3.txt

Adding stuff to the end of a file

5. Redirect to another process or to nowhere

The examples above cover redirecting output to a file, but you can also redirect outputs to other processes or dev/null.

Sending output to other processes is one of the most powerful features of a shell. For this task, use the | (pipe) symbol, which sends the output from one command to the input of the next command:

ps -ef | grep chrome | grep -v grep | wc -l

21

The above example lists my processes, filters any that contain the string chrome, ignores the line about my grep command, and counts the resulting lines. If I want to send the output to a file, I add > and a file name to the end of the chain.

Finally, here is an example where I want to ignore one of the outputs, the STDERR:

$tar cvf my_files.tar file* more-non-existing*

file1.txt

file2.txt

file3.txt

tar: more-non-existing*: Cannot stat: No such file or directory

tar: Exiting with failure status due to previous errors

Because the tar command did not find any files with names starting with more-non-existing, some error messages display at the end.

Suppose I create some scripts and don't care about seeing or capturing these errors (I know, in real life, you should prevent and handle the errors, not just ignore them):

$tar cvf my_files.tar file* more-non-existing* 2> /dev/null

file1.txt

file2.txt

file3.txt

The /dev/null is a special device file that is like a "black hole": What you send there just disappears.

[ Download this guide to installing applications on Linux. ]

6. Use redirection in a script

=== SUMMARY OF INVESTIGATION OF chrome ===

Date/Time of the execution: 2022-03-25 18:05:50

Number of processes found.: 5

PIDs:

1245475

1249558

1316941

1382460

1384452

This very simple script does the following:

- Line 3: Executes a command in the operating system and saves to the variable DATE_TIME.

- Line 6: Runs the

pscommand and redirects togrepand to a file.- Instead of sending the output to a file, I could send it to a variable (as in line 3), but in this case, I want to run other actions using the same output, so I capture it. In a more realistic situation, having the file could also be useful during development or troubleshooting, so I can more easily investigate what the command generates.

- Line 8: Runs additional commands, redirects the outputs to

wc, and assigns the result to a variable. - Line 9: Uses

awkto select only column 2 from the output and sorts it in descending order (just for the sake of adding another pipe).

Wrap up

Those were some examples of redirecting STDOUT and STDERR. Putting all this together, you realize how powerful redirection can be. By chaining individual commands, manipulating their output, and using the result as the input for the next command, you can perform tasks that otherwise could require you to develop a script or program. You could also incorporate the technique into other scripts, using everything as building blocks.

About the author

Roberto Nozaki (RHCSA/RHCE/RHCA) is an Automation Principal Consultant at Red Hat Canada where he specializes in IT automation with Ansible. He has experience in the financial, retail, and telecommunications sectors, having performed different roles in his career, from programming in mainframe environments to delivering IBM/Tivoli and Netcool products as a pre-sales and post-sales consultant.

Roberto has been a computer and software programming enthusiast for over 35 years. He is currently interested in hacking what he considers to be the ultimate hardware and software: our bodies and our minds.

Roberto lives in Toronto, and when he is not studying and working with Linux and Ansible, he likes to meditate, play the electric guitar, and research neuroscience, altered states of consciousness, biohacking, and spirituality.

More like this

Red Hat Learning Subscription Course reimagines virtual training

More than meets the eye: Behind the scenes of Red Hat Enterprise Linux 10 (Part 5)

OS Wars_part 2: Rise of Linux | Command Line Heroes

Are We As Productive As We Think We Are? | Compiler

Browse by channel

Automation

The latest on IT automation for tech, teams, and environments

Artificial intelligence

Updates on the platforms that free customers to run AI workloads anywhere

Open hybrid cloud

Explore how we build a more flexible future with hybrid cloud

Security

The latest on how we reduce risks across environments and technologies

Edge computing

Updates on the platforms that simplify operations at the edge

Infrastructure

The latest on the world’s leading enterprise Linux platform

Applications

Inside our solutions to the toughest application challenges

Virtualization

The future of enterprise virtualization for your workloads on-premise or across clouds