A leader's most important role is to build an organization that can not merely function but thrive, even if we are not present. A large part of that lies in creating a place where people feel they are part of something great—bigger than and beyond each individual.

"No man is an island entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main" - John Donne

This requires recognizing that a workplace is a collection of communities with multiple overlapping relationships in which the participants grow, continually unlocking their potential and contributing their skills and energies to others and the broader organization.

[ Learn the real secret to retaining talent. ]

This article considers four interlocking parts of that equation: management, individuals, mentoring, and communities. I will begin with the question of why—addressing the things that appeal to the intrinsic motivators of autonomy, mastery, and purpose for the people you manage and lead. I will also describe other ways to enhance communication across the organization by supporting and encouraging other, less formal systems, such as mentoring and communities of practice, to enrich learning, growth, and professional fulfillment.

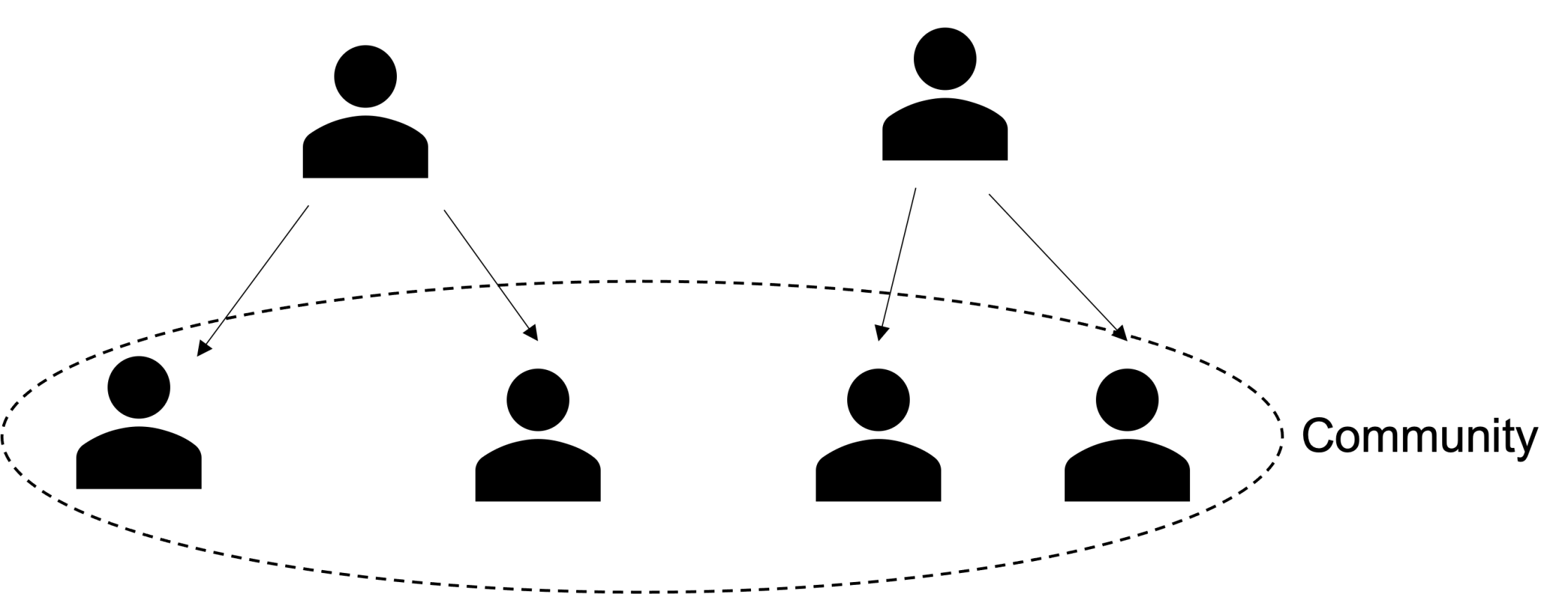

In any large organization, there will be parallel worlds and lines of communication:

- Formal, org-chart-driven lines reflect a person's job role and position in the organization. We are primarily aligned to our value stream's small, long-lived teams. Our tribal identity is to that business value stream.

- Informal, often technology- or skill-driven communities form to help practitioners expand their knowledge of and familiarity with their craft. Secondarily, we are aligned to a community relevant to the vertical part of our T-shaped skill sets and specializations.

- Cross-organization mentoring relationships form either spontaneously (informally) or through planned mentorship programs (formally).

A healthy organization promotes, encourages, and builds up all three lines of communication.

I will start with looking at the first, org-chart-driven lines of communication, particularly regarding what it means to be a successful leader and manager.

1. Leaders and managers

If our role as leaders is to inspire purpose, create alignment, and set teams up for success by unlocking their potential, what does this mean for being a manager?

Something I read years ago struck me as true and has stayed with me since:

"At the end of the day, people won't remember what you said or did, they will remember how you made them feel." — Maya Angelou

How do you want to be remembered after you or your team members have moved on to other things?

The two halves of leadership

Leaders and managers have a job to do: Turn work and effort into meaningful value and deliver it to our customers, clients, and stakeholders.

But this is only the what you do half. What of the other half, how you do it? Could this be equally important for the success of your business?

[ Use the 5 elements of digital transformation to bring balance to your organization. ]

If manager and leader success were a measure of the balance between these two halves—a balance that leaders learn to maintain over time (especially during challenging and stressful periods)—what would it look like, and how can it be created? What skills, competencies, confidence, and panache must we master to be great managers and leaders? How can we become the sort of managers and leaders who are remembered for making team members feel inspired, trusted, valued, and fulfilled in realizing and expressing their potential?

To start, let's look at what it's not. It is not the role of the leader and manager to do and be responsible for everything and issue instructions and commands for others to follow. A leader cannot do and know everything. Nor should they even try.

Be across the work, not in the work

What are the practical ways of letting go to empower others? Three simple principles point the way: build trust, set boundaries, and get out of the way.

- Build trust: This starts with relationships. And relationships are built through communication, particularly the kind that is both sharing and listening. Can you invest the time to really listen to those you lead, resisting the urge to tell, correct, or even teach? Can you listen in a way where the other person feels genuinely heard and understood? From here, build the relationship of trust through setting expectations, giving genuine feedback, and offering real responsibility.

- Set boundaries: All workable relationships must be bounded insofar as the trust between people in any relationship is framed by a set of implicit or explicit expectations. Begin to understand this and practice it explicitly through collaboratively creating ways of working that reinforce the values and principles of your teams. Build on these by providing details of the behaviors that are acceptable or not per context (for instance, through team agreements). Through retrospection, continually review and evolve the values, principles, and behaviors as your teams and relationships evolve.

- Get out of the way: Step back and let the teams work, experiment, learn, and grow within the boundaries created. The wise leader knows that a healthy space is one where humans are free to grow and learn within clear bounds of expectation. Give permission for communities to form, such as communities of practice where members' natural inventiveness, creativity, and novel discovery can thrive. Create such conditions with clear expectations (trust) and aligned boundaries, and encourage the community, inspecting the outcomes where you amplify the value outcomes you are looking for. Rather than direct instruction, spend time looking into the conditions you can create for your team members to thrive independently. Support and coach them, rather than telling and dictating, to encourage the informal foundations of communities.

2. Team members

Regardless of position or role, everyone is a team member—a member of a functional team, a reporting team, and a team of peers. Within your job, you are a subject matter expert of some kind, whether you're an executive, manager, engineer, architect, designer, developer, tester, business analyst, researcher, scrum master, product owner, and so on.

Is it enough just to deliver, deliver, deliver in your functional role? What else makes you feel inspired, purposeful, and with a growing sense of fulfillment?

Along with the extrinsic motivators of material loss or gain, there's—arguably just as significant—a set of intrinsic motivators that drive us forward with an inherent willingness to grow and persevere: autonomy, mastery, and purpose.

- Autonomy is the independence and permission to self-govern within the scope of your role and responsibility. It enables you to create and develop your career, confidently express your talents, and grow those talents in collaboration with others.

- Mastery is the desire to improve your craft, talents, and skills to express who you are and what you love to do toward delivering value outcomes for stakeholders, customers, and clients.

- Purpose is alignment to a higher goal or aspiration that is currently beyond you while also potentially achievable. It is the feeling of being part of something bigger than yourself.

[ Learn essential career advice from 37 award-winning CIOs. ]

If you lack autonomy, mastery, or purpose in your work, look to create them. If you are not clear on the why behind what you do and for whom, seek to find out.

- Managers and leaders: Check in with your people: Are these motivators present or absent? Can you provide the purpose, the why for those you lead, that is inspiring, compelling, and meaningful? Use your management and leadership skills, resources, and capabilities to generate environments where autonomy, mastery, and purpose are present for your teams and the people you lead.

- Individuals and team members: Be coachable. Take the trusted feedback, insights, and responses from your manager, peers, customers, and clients as learning opportunities. If you don't already have one, seek out and find a mentor. In these ways, you grow in your confidence, experience, and eminence, contributing direct and incidental value to the business and communities you are part of. This defines the development of your professional self and your career.

3. Mentors

Your experience makes you wealthy. Give it away.

Mentors are another kind of leader that helps build the deep relationships that help people grow in an organization. Mentors provide a unique perspective to team members—a perspective from outside the organization that helps people understand the broader organizational context in which they work. If a person wants to really feel a part of something bigger, they need to understand how other parts of the organization contribute to the whole. Having a mentor in a different part of the organization is a great way to share this perspective.

There are many forms of mentorship and ways to carry out the mentoring relationship. Perhaps the simplest form of mentoring is career mentoring, where someone at a higher level (one or two levels above) provides help and guidance to a person at a lower level. Advice may include how to navigate the organization, where to find opportunities, and chances for collaboration on cross-organizational projects that can build a person's reputation.

You can mentor another person in a technical area (especially in an apprenticeship setting) or help someone achieve a specific personal or professional goal, like obtaining a professional or industry certification you have achieved.

The most important thing is that a mentoring relationship is two-way—the mentor gains as much from the mentee as the other way around. To be a good mentee, you must provide good feedback on the process, the opportunities, and what you see in the organization. That's how the relationship grows and develops as it becomes more useful for both people.

Who can become a mentor? Nearly anyone at any level! Do you have experience with the company where you work? Are you connected to a wide network of colleagues and subject matter experts? Do you enjoy seeing others grow and being part of that growth through sharing your wisdom and experience? If so, consider being a mentor and build your organization's cross-connections.

4. Community

Humans are naturally social and tribal. A sense of history, folklore, and belonging are important to us. In many respects, this sense of belonging, of being part of something, is essential for our ability to plan, organize, and create outcomes.

Communities are an expression of this. Formed from intent, they are based on an aligned and shared purpose. How can you leverage communities to benefit your and your business' growth? Can you bring together the leaders', managers', and team members' intentions, visions, and desires in some meaningful way that self-sustains and grows?

Communities of practice

Sometimes known as guilds, communities of practice (CoPs) form based on a shared interest and a common desire for autonomy, mastery, and purpose. Belonging to a CoP can make your profession more enriched and fulfilling. Membership is variable, with people taking on different roles as needed and evolving over time. People can leave and join (and perhaps rejoin) CoPs as their jobs and work activities change. A CoP tends to last only as long as people feel they are receiving something positive from it, and it will grow only as long as people think they have an opportunity to contribute to others.

An example is technology-based CoPs, which often form organically when a new technology is available or adopted. An early and influential community was the Homebrew Computer Club, an early CoP around building home computers from (then-new) 8-bit microprocessors. That community had an outsized effect on the development of the personal computer industry as a whole, as its members formed Apple Computer and Osborne computers (which pioneered the portable computer).

[ Looking for tips to improve your communities? Download The open organization guide to IT culture change. ]

At IBM, we have been informally forming CoPs for years. In the early years of WebSphere Automation, several CoPs arose in the Lab Services organizations around newly acquired products such as CrossWorlds, DataPower, and Ilog to help new practitioners come up to speed on these new products. A current example of an IBM CIO software engineering CoP is the XP Farm, a community of practice dedicated to the craftsmanship and mastery of extreme programming and agile software development techniques.

An advantage of this community approach is that people learn more quickly from solving real-world problems than in abstract academic situations. Having a team of practitioners to ask questions about when you run into new issues helps provide insight into problems from different perspectives, as well as building connections between people that persist even as people move on to other roles and products.

Augmenting the CoP through mentoring

That leads me to another type of CoP that is enormously beneficial to practitioners: a professional certification community of practice. This type of CoP forms an interesting bridge between community and mentoring. It builds a community of people that help each other become recognized as leaders in their profession.

For instance, IBM has an internal certification program for its architects based on the TOGAF certification. Demonstrating and documenting the skills, education, and experience to meet this certification can be challenging for someone new to it. This makes a certification CoP important for architects who want to achieve this certification. Learning from those who have already been through the process and working with others in the same position creates a better experience for everyone.

Starting a community of practice

Voluntary, open invitation CoPs are powerful for sharing lessons across value streams. CoPs are Darwinian by design, in that they are not artificially kept alive: Their survival depends on their fitness of purpose and ability to evolve. They run as regular meetups to share learning, understanding, and social proof and to innovate across teams.

To launch a CoP:

- Organize by region; localize around a shared purpose.

- Seek out the innovators and early adopters and invite them to join.

- See who turns up.

- The law of mobility applies: Attendance is voluntary.

- Keep the change gradient low as experiments are proven in your context within an agreed risk appetite.

- Encourage organic growth, staying true to the founding principles.

Conclusion

This article looked at leaders/managers, individual team members, mentors, and communities of practice. It outlined the purpose of each and distinguished the potential benefits for people and the broader organization when specific intersections of these groups take place in a conscious way designed around openness, trust, learning, alignment of expectations, and psychological safety. These intersections, expressed through communities, allow the intrinsically motivated emergence of individual talent and skill development, which collectively promote health or wellness within the organization.

[ Learn more about motivating your team with this advice from IT leaders. ]

In this, we see that we are all within a set of connections. From our specific roles, we can participate in this organizational wellness as team members, leaders, managers, mentors, and mentees.

This article originally appeared on LinkedIn and is republished with permission.

About the authors

Kyle is currently the CTO of Cloud Architecture leading the Garage Solution Engineering team for IBM Cloud. Before that, he was the lead software group consultant for the WebSphere Virtual Enterprise products, the DataPower SOA Appliances, IBM PureApplication System, and a host of other products. He specializes in applying emerging technologies to the business problems of Fortune 500 companies. He's also an avid writer, having authored and co-authored 10 books. Kyle has also written over 100 articles and conference papers on subjects running from Design Patterns to cloud development. He also blogs regularly on Medium.

A passion for the culture of organizations - particularly in the relationships between people, technology, and how they can come together to create value outcomes - Shane is an enterprise and professional coach, facilitator, and trainer with a background in large-scale software engineering solution design, implementation, and delivery. Before joining IBM in 2015, Shane worked as an organizational transformation consultant with numerous start-ups, including Microsoft, The Economist, and The Royal Bank of Scotland. Shane lives in the south of England with his wife and two children.

More like this

Red Hat Learning Subscription Course reimagines virtual training

Red Hat Learning Subscription Course: Skills for the future

Becoming a Coder | Command Line Heroes

Compiler: Re:Role | The Designer And The Blueprint

Browse by channel

Automation

The latest on IT automation for tech, teams, and environments

Artificial intelligence

Updates on the platforms that free customers to run AI workloads anywhere

Open hybrid cloud

Explore how we build a more flexible future with hybrid cloud

Security

The latest on how we reduce risks across environments and technologies

Edge computing

Updates on the platforms that simplify operations at the edge

Infrastructure

The latest on the world’s leading enterprise Linux platform

Applications

Inside our solutions to the toughest application challenges

Virtualization

The future of enterprise virtualization for your workloads on-premise or across clouds